Source: Marin Katusa, Casey Research (12/16/11)

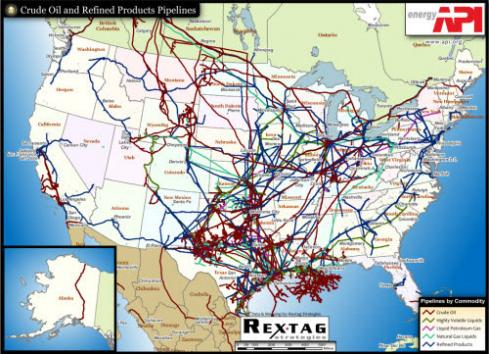

"From the heated nature of the Keystone XL debate, one could be forgiven for thinking that long, high-volume pipelines are something new to America. In truth, there are now over one million kilometers of oil and gas pipelines crisscrossing the United States."

The Keystone XL ruckus shone a light on pipelines like never before. From the heated nature of the debate one could be forgiven for thinking that long, high-volume pipelines are something new to America. Really, that couldn't be further from the truth: The United States built its first pipeline in the 1840s, and there are now more than a million kilometers of oil and gas pipelines crisscrossing the country.

When it comes to moving oil and gas across land, pipelines are far and away the best choice. They are the safest transportation mechanism for the people who work in the industry and for the environment, and they are the most efficient, meaning they burn less energy to move all that fuel than the other options. And really, there are not many other options. In a few places oil is moved by rail, but rail is slower and less energy efficient, and trucks are too small. Pipelines are it, and have been since that first pipeline moved gas from Pennsylvania to New York City to light street lamps. Every hour the world consumes a million tonnes of oil and a quarter of a trillion cubic meters of gas—and almost all of it moves, at one point or another, through a pipeline.

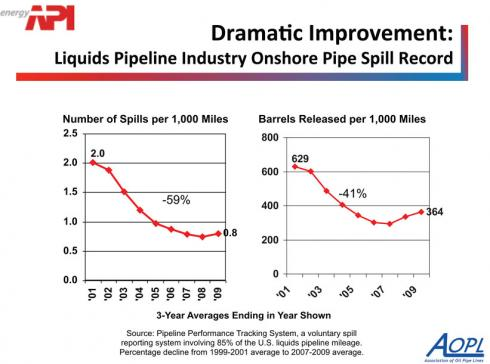

The pipelines in North America are among the safest in the world. According to the Canadian Energy Pipeline Association, the average annual loss of liquid fuels from its pipelines is two liters for every million liters moved. In other words, Canadian pipeline companies have earned themselves a safety record of 99.99%. American operators are similarly laudable. The American Petroleum Institute tracks pipeline performance; the charts below show that not only are things pretty darn good, they also continue to improve.

Accidents do happen. The primary cause is corrosion in old pipes. But think about that for a second: The fact that old pipelines can become corroded and develop leaks is not an argument against pipelines—it's an argument for new pipelines. The charts above show just how much the pipeline industry has improved its spill record in just nine years. In that context, consider this: 41% of the pipelines in North America were built in the 1950s and 1960s, while another 15% are even older than that. Not surprisingly, technology has advanced leagues since then, and unfortunately many of those old pipelines were build using protective coatings that we now know break down over time.

So old pipelines need to be replaced with newer, safer ones, but that is only one side of the story. The other side is that North American oil and gas production is on the brink of a major upswing, and we need to add significantly to our pipeline network in order to move these huge new volumes of oil and gas from the field to the market.

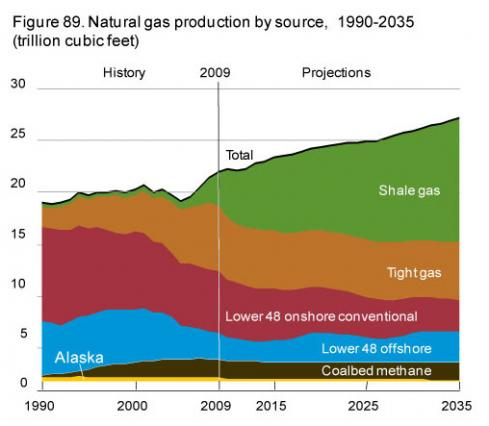

Most energy-market watchers are aware of the natural gas boom, borne out of trillions of cubic feet of gas discovered in the continent's shale deposits. Production has already risen, but the best is yet to come. In the coming decades shale gas will come to account for some 40% of America's gas production and will be the reason the country's gas output is expected to climb come 30% instead of declining. These trends are illustrated nicely in the chart below, which we borrowed from the US Energy Information Administration.

It ain't just gas that's booming. Oil production in North America is also rising, and if any small portion of the continent's shale oil deposits can be put into production economically, then output will shoot skywards. Right now America's total proven onshore oil reserves stand at roughly 15 million barrels. The oil that geologists believe lies within America's shale deposits dwarfs that number: estimates for the Bakken, Eagle Ford, and Marcellus shales average 20billion barrels each. Now, these barrels are not "proven," which describes reserves expected to be economic. But the oil is there and, as Canada's oil sands have so clearly shown, uneconomic deposits turn into black gold when the price of crude rises. Those oil sands are the other reason North America's oil output is climbing: The oil sands are already pumping out 1.5 million barrels of crude oil per day (bpd), with production expected to double by 2020 and then rise to 3.7 million bpd by 2025.

All of this domestic oil and gas is a blessing. People may not love the idea of oil and gas wells in their beloved homeland, but the only other choice is to continue buying oil from Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Venezuela, Iraq, Angola, Colombia, and Algeria. The list speaks for itself—all are countries with US relations ranging from delicate to downright difficult and unstable.

Finally, whether or not one wants to believe that we need all this oil, the fact is that we do. North America is addicted to fossil fuels. That addiction needs to be treated, but the transition will take a long time, especially because none of the alternative energies developed to date stand the test of economics. Until those options improve and then expand, even environmentalists will need to heat their homes, buy food and goods transported on trucks and rail, use cars, buses, and planes to get around, and plug in their electronics. And don't forget that oil is not just used to make fuel—oil is also a major ingredient in plastics, rubbers, fertilizers, paints, dyes, detergents, synthetic fibers like polyester and nylon, and makeup. We really do operate in a world that turns on oil and gas.

Let's summarize. We need oil and gas. The safest and most efficient way to move these fuels across land is using pipelines. Old pipelines are prone to leaking, while new pipelines leak far less often. And we don't have enough pipelines as it is, because oil and gas production in North America is about to power up. These facts point to one conclusion: North America needs new pipelines.

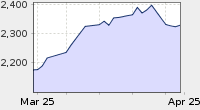

As plans for new pipelines are announced, the markets will move. We saw a perfect example of this just last week, when the price of North America's crude oil benchmark, West Texas Intermediate (WTI), shot up 3.2% in a day in response to Enbridge's (T.ENB) announcement that it is buying the other half of the Seaway pipeline and will reverse its flow, to take oil from the oil hub at Cushing, Oklahoma, to the Gulf Coast. Until now the Seaway pipeline has taken 400,000 barrels of oil each day from the Gulf Coast to Cushing, where a supply glut created by increasing production from (where do you think?) the oil sands and the Bakken shale has pushed WTI to a record deficit compared to Europe's benchmark crude, known as Brent North Sea. A near-term way to reduce that supply glut was enough to make oil traders giddy. The next day, another piece of pipeline news boosted WTI's fortunes even further: the company behind the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, TransCanada (T.TRP), is pushing for permission to start building the southern portion of the line, from (you guessed it) Cushing to the refineries on the Gulf Coast, as soon as possible. Obama's administration said TransCanada has to reroute the Nebraska part of Keystone XL but voiced no objections to the rest of the route, so the company is hoping to get started on the supply-glut-easing portion now.

America needs new pipelines, and where there's a need there are investment opportunities. The energy sector is a complex beast, involving a multitude of factors from international relations to pipeline plans, and it is more than a full-time job to keep on top of it. Luckily, the Casey Research energy team has several full-time jobs devoted to understanding what is happening, why it matters, what it will mean for the markets, and how we can profit from it. As North America's oil and gas production rises, investment opportunities will arise with it, ranging from explorers to pipeline operators to refiners, and we can help you identify the right vehicle for you to ride the wave.

Marin Katusa, Casey Research

No comments:

Post a Comment